How to Design for Unpredictable Holidays

While most consumers busily put the finishing touches on holiday decorations and wrap last-minute presents, industrial designers like Steve Chininis are half-way into designing next year’s holiday season. In fact, some of them may already be hard at work for 2023, he said.

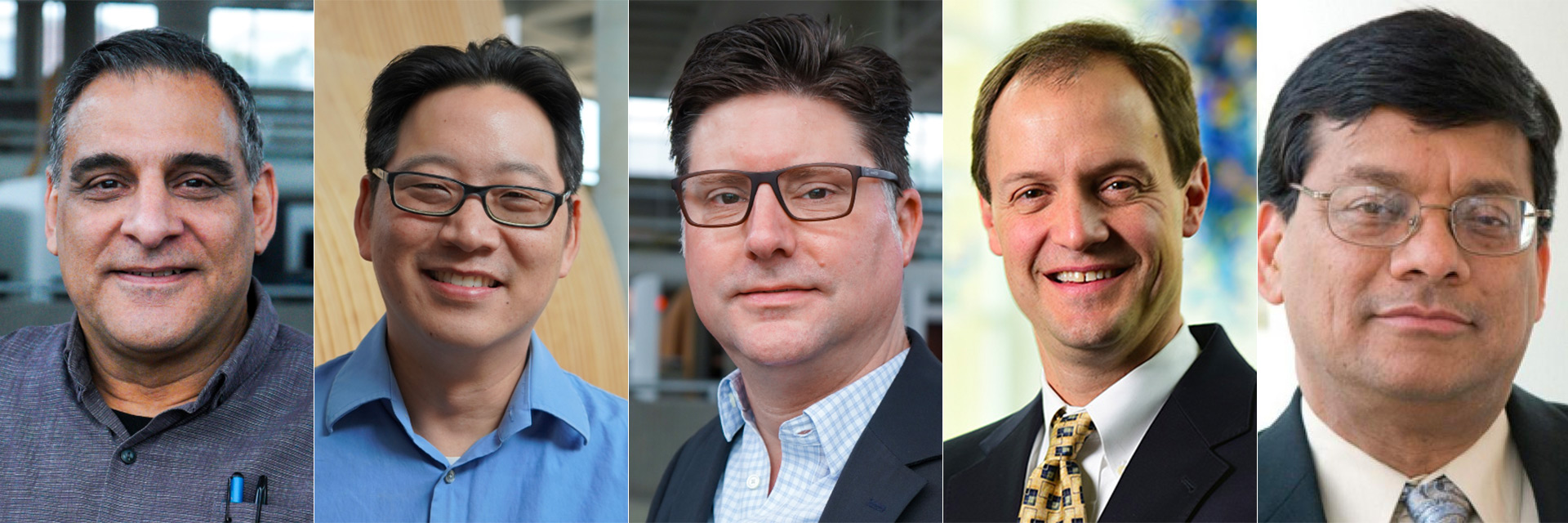

“Once the design is done and everyone’s approved it, and it’s full speed ahead, it can still take more than a year to produce a product,” said Chininis, a professor of practice for the Georgia Tech School of Industrial Design. “There’s all kinds of backlogs that can happen.”

As much as consumers felt the effects of supply chain backlogs during this year’s holiday season, industrial designers and entire holiday merchandise teams are dealing with them, too.

Designing Holiday Products

“I’ve designed products for design firms and toy companies like Hasbro as a product designer. The business I’m in now, and have been for many years, is as an inventor in the toy industry. I come up with a toy idea and take it to a toy company. They might say, ‘We want this, it’s perfect for our Easy Bake Oven line.’ And then they take the design and finish the product development in-house,” Chininis said.

In either design situation, the toy companies plan their merchandise lines far in advance. “So if inventors come in from outside the company and show up with a good idea, it won’t disrupt their plan.”

“They might say, ‘We want to do that space toy for 2023 because that’s the theme we have in mind, and we want it to have a specific mechanism, and it’s amazing because it does something new’,” he said. “Then when the toy comes out a year and a half later, you’re either delighted or terrorized by what the company did,” Chininis said with a laugh.

Stores that sell home goods tend to design their holiday merchandise a year in advance, said Wayne Li, a professor of practice of design and engineering, and the director of Design Bloc.

“Every three months they come out with a new collection of products,” Li said. “Usually there’s a spring, summer, fall, and holiday season collection.” Industrial designers that work for these retailers typically start the design process in September or October for the following holiday season, he said.

Li worked for Pottery Barn as a senior designer in the product development group, and said the seasonal design process involves constant feedback from company executives and other product experts. Marketing staff and production sources work side by side with designers to bring holiday products to store shelves.

As part of the product team, marketers inform the designers about consumer trends and purchasing trends, said Tim Halloran, a senior lecturer for the Scheller College of Business. “They tell the product designers what they’re seeing in the marketplace, what they anticipate to be the hot colors or the hot products of the season, or they suggest tweaks to products based on consumer research,” Halloran said.

Then for three to five months, designers work on product ideas and test their designs through small batches of manufactured samples.

After the company makes final style and production cost decisions, “then from that point on, from month six through month 12, it’s all about production,” Li said. If the product is manufactured overseas and freight-shipped on a boat, and then distributed from the Port of Entry to stores across the country, “that can take up the last two months of the production window.”

Supply Chain Hiccups

Some of this year’s holiday merchandise was probably designed before the pandemic and subsequent supply chain issues, said Kevin Shankwiler, a senior lecturer and the undergraduate program coordinator for the School of Industrial Design. “Then they went into sourcing and production, and that’s when the problems really hit.”

“I was just talking to a friend here in town, he’s the world’s largest supplier of dollhouse items. He’s been a client for years,” Chininis said. “He was telling me that he used to pay about $2,200 for a shipping container. Now it’s $23,000.”

“That’s what you have to pay to get a container that you don’t know for sure is going to land and get emptied,” he said. “So then, if it lands and gets emptied, is there a warehouse that can take it? And then are there trucks that can bring it to you? Those two things are also weak right now.”

Another example of supply chain hiccups affecting consumers is the microchip shortage, Shankwiler said. “Automobile manufacturers are having to react, because there’s not enough microchips to control all the specific functions of the vehicles. Ford Motor Company, recently decided to invest in their own chip production as a result.”

Li said certain holiday products, like moving toys or musical greeting cards, also depend on computer chips. They’ve become a good example of the “here versus there” paradigm of product design because of this year’s supply chain issues, he said.

“We always tell our students to look at the the entire carbon footprint, or the sustainability of a product. What can be produced over here, and what must be produced over there? That paradigm includes components your company has to make from scratch, and things that are procured, like off-the-shelf parts,” Li said.

The decisions industrial designers make in the early stages of the design process can have significant impacts later down the supply chain, Shankwiler said. “If we make a decision about a color or a material that suddenly becomes unavailable, or is very specialized, the options for finding an adequate substitute are far fewer.”

That’s why he teaches students in his parametric modeling class to accommodate their designs for product components. “I have the class create a smartphone case, and it’s always going to be a battery-powered case. It’s got to hold the size of a battery. And then halfway through the project I come back to the class and say, ‘Engineering change. It’s a bigger battery now.’ And they have to go back and redo their design.“

Uncertain Times and New Needs

Part of understanding consumer trends is understanding needs that aren’t being met, Halloran said. “I would argue there are new needs now because the pandemic has changed our world. We’re working from home more, we have different needs in the house.”

“And that’s why we’ve seen crazy prices in home construction and renovation,” he said. The realization that consumers needed more function, comfort, or beauty out of their homes, “somewhat snuck up on marketers.”

It was certainly hard for marketers to predict product trends this holiday season when they were working on it 18 months ago, Halloran said. “Part of me thinks that we were maybe a little conservative and cautions because people just didn’t know where we were going. Marketers try to figure out where we’re going, and I think this pandemic has thrown us all for a loop.”

“One thing I’ve noticed is less variety on store shelves,” Shankwiler said. That means industrial designers may see less of their efforts go to market as a result of the supply chain issues in 2021, he said. “They’re probably also looking at having to significantly ramp up their efforts once the backlog clears up, to get products back on shelves again.”

Vinod Singhal, a professor and the Charles W. Brady Chair of Operations Management at the Scheller College of Business said 90 to 95 percent of holiday merchandise is not manufactured in the US. The lack of variety on store shelves also comes down to production cost, he said.

“China and Vietnam are the biggest manufacturers of decorative items,” Singhal said. “So when you think about it, the logjam we’re seeing now, these products are stuck somewhere on a ship.”

Big box retailers, like Walmart, Home Depot, and Target anticipated the logjam, he said. Rather than loading their containers on ships that carried other companies’ merchandise, they hired their own, exclusive ships.

“Walmart and Home Depot recently shared their earnings and they’re doing really well,” Singhal said. “And one of the reasons they’re doing well is that they have the power to say ‘This ship is only for Home Depot.’”

“But if you’re a small retailer, you probably only want one container of product. You can’t rent your own ship, you have to put your container on a ship with everyone else’s, and you have to wait in line till your container is downloaded, put on a truck, and so on,” he said. “A lot of these small retailers are going to take a big hit.”

Future Holiday Seasons

“Companies and designers are learning to be a bit more flexible,” Shankwiler said. “But also bringing elements of the supply chain closer to them, so they have more control.”

“One of the risks you have with offshoring a lot of production is that there’s a high risk. If there’s a disruption way over there, it’s really going to affect you over here. That’s exactly what we saw this year,” he said.

“If you’re thinking about supply chain and you’re used to going to China to make it, and it gets put on the ship and comes over here and whatnot, then [as a product maker] you’re thinking, ‘I wonder if there’s someone here in Georgia I can get to make it’,” Chininis said.

“In a way it’s doing something that industrial designers wanted to do years ago. It’s bringing the supply chain closer and regionalizing the supply chain. But it’s doing it under duress,” Chininis said.

Singhal said the advent of hyper-local sourcing will promote economic development in North America. “The question is, can you do it,” he said.

“If you want to assemble a computer in the US, you can find people who can do that, sometimes. And you can pay them the price that they ask for. So your costs tend to go up,” Singhal said. “These trade wars, the geopolitical issues, and now the supply chain logjam, will put pressure on companies to start thinking about doing things closer to home.” Mexico and South America are also “close-to-home” manufacturing options, Singhal said.

“But the problem is you run into the economics of people willing to pay another 30 percent for the same toy made in the US versus China,” he said.